Churchill, Creativity & AI

May 28, 2025“The history of INNOVATION is the BED, the BUS and the BATHTUB.” Creativity happens when you least expect it. We try our best to conjure up creativity in design thinking workshops or structured team brainstorms – but the truth is, the best ideas often happen in bed, while you’re on the bus, or taking a bath.

I like this excerpt from a 13-minte “How Stanford Teaches AI-Powered Creativity in just 13-minutes” by Jeremy Utley, Director of Executive Education at Stanford University's celebrated d.school.

I’m often talking about how we should think about AI more like an IA.

An “Intelligent Assistant” not “Artificial Intelligence.”

I have 31- assistants I check in with each day. Each one is focused on a narrow task of storytelling or audience analysis and they’re helping thousands of IBMers to do their jobs better.

They’re just assistants who can be trained as digital twins to mirror the tone, preferences and behaviour of whoever is using it.

No more generic scripts or boring client success stories.

Folks are using these assistants to create high levels of personalisation – just like Churchill did when he was in the bath.

The average person’s vocabulary contains around 25,000 words.

Churchill’s has been estimated at 65,000. He loved words and understood the power of rhetoric, able to perfectly place small words within short powerful sentences which resonated deeply with his audiences.

He once said, “Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so precious as the gift of oratory. He who enjoys it wields a power more durable than that of a great king”.

Much has been written about Churchill’s words and achievements, but little has been written about his communication techniques. As a young man, Winston’s ambition was the be a “master of the spoken word”, something that he achieved through constant practice.

He obsessed over every word and even went as far as visualising every speech in advance, anticipating where he was likely to be interrupted so that he would always have a strong response prepared.

Churchill despised speakers who were unprepared. He felt like they were neglecting their responsibilities and disrespecting their audience. He promised himself that he would never act like the kind of orator he detested, who “before they get up, do not know what they are going to say; when they are speaking, do not know what they are saying; and when they have sat down, do not know what they have said”. When Churchill spoke, nobody was in any doubt about what he said or what he meant.

The consummate performer, Churchill would rise, when recognized by the Speaker, with two pairs of glasses in his waistcoat. Perching the long-range pair on the end of his nose at such an angle that he could read his notes while giving the impression that he was looking directly at the House, he gave every appearance of speaking extemporaneously.

If the occasion called for quoting a document, he produced his second pair and altered his voice and manner so effectively that even those who knew better believed that everything he said when not quoting was spontaneous.

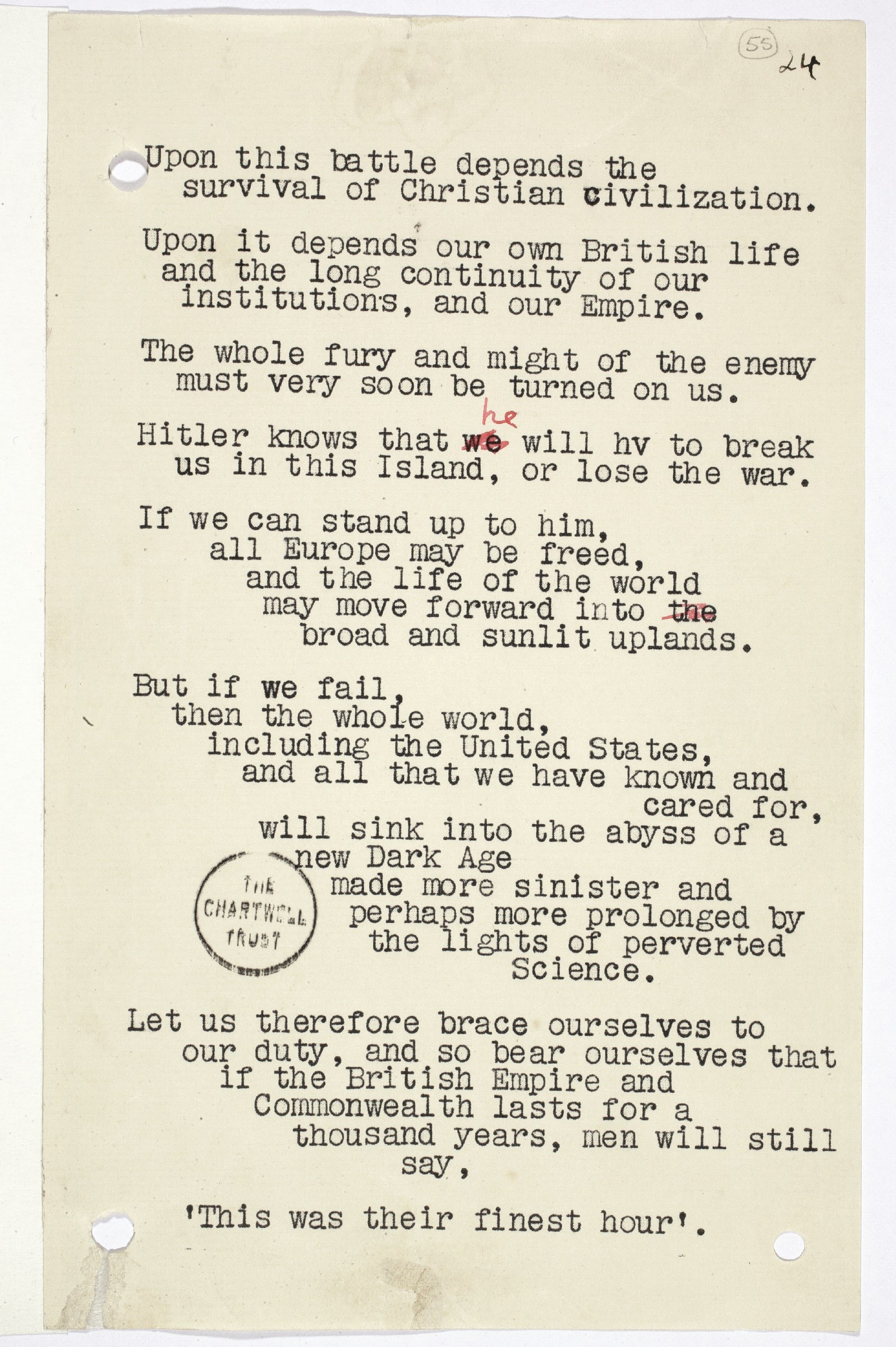

To aid in the flow of delivery, he would set the text of his speeches in what his staff called “psalm form” — a practice that may have been inspired by his love of the Old Testament. To these haiku-esque blocks, he would add notes for their delivery: where to pause and where to expect an ovation; which words and letters to emphasize; even where to appear to stumble a bit, grope for a word, and “correct” himself. Churchill knew that a flawless, robotic recital would put people to sleep and that the more naturalistic a speech seemed, the more tuned in his audience would be.

Churchill had a “secret side” concerning how he went about delivering his speeches in Parliament. Once he had the final version of a speech, he typed it on pieces of paper measuring around 4” x 8”. The text was set in broken lines (like a Psalm) to aid his delivery, in what he called “speech form.” It was assumed that these were notes on his topic where in actual fact is was his speech completely written out and delivered word for word.

Churchill put a lot of effort into writing a short speech.

Mark Twain allegedly said, “It usually takes me more than three weeks to prepare a good impromptu speech.”

Churchill loved this quote. He often quipped to his assistants, "I'm just preparing my impromptu remarks" when they caught him writing a few lines for a “spontaneous” speech he was planning to give.

Moral of the story?

We are now living in a time when every single person, no matter their age, experience, or academic qualifications – has access to the quality of assistants that was previously only available to CEO’s and world leaders.

AI is not here to write your story or your speech for you. Stop using it just to write emails, create click-baity posts or synthesise large documents because you can’t be bothered reading them.

Start treating AI more like an IA .

Train it to understand your voice, your likes, your dislikes, your favourite words, phrases and behaviours.

I know we’re all getting a bit tired of AI posts on Linkedin, but that’s often because we haven’t found a way to make AI work for us yet.

YouTube “How to create a Custom GPT”. You’ll have your own assistant up and running in 20 minutes.

Churchill once said, “Writing is an adventure.”

Try treating your AI journey like an adventure.

Be careful which guide you follow. (There’s a lot of bad ones on this platform).

Find the path that works for you.

And have fun.

Now go take a bath…